(EMPIRE NEWS NETWORK (ENN)— SAN BERBARDINO, CA—In honor of former Assemblywoman Wilmer Amina Carter, Assemblymember Eloise Gómez Reyes (D-San Bernardino) is continuing her legacy by hosting the 2nd Annual 30 Under 30 event. The goal of the 30 Under 30 Award Ceremony & Art Showcase is to honor the accomplishments of young adults 30 or younger who live or work in the 47th Assembly District.

“The 30 Under 30 event is a very special event for the 47th Assembly District. This event honors young adults in our district who continue to break down barriers for themselves and others,” said Assemblymember Reyes. “It is an honor to recognize such service driven young adults who work hard every day to give back to their community, whether it is through the arts, entrepreneurship or community activism. Congratulations to this year’s 30 Under 30.”

Over 80 nominations were received.

“The process to select the 30 was difficult because there were so many extremely well qualified nominees. I am proud of the final selections,” said Assemblymember Reyes.

30 Under 30 Honorees

Alazzia Gaoay

Alazzia Gaoay

Alazzia Gaoay is the engine driving the growth of the Fontana Chamber of Commerce’s online community. She develops relationships and keeps the community engaged through social media and digital marketing strategies and management. Her conversational style has catapulted the Chamber’s following by over 600% in the past year. She oversaw a complete rebrand of the logo, newsletter, website, and social media. Alazzia is a gifted photographer and artist who has applied those talents to make a real impact on the work accomplished at the Chamber of Commerce. Alazzia has her B.A. in Mass Communications from CSUSB.

Anthony Victoria

Anthony Victoria

Anthony Victoria is a former reporter for the Inland Empire Community News and newly-appointed Director of Communications at the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ). As a native of the City of Rialto, and a graduate of Eisenhower High School, San Bernardino Valley College and the University of California, Riverside, Anthony has built a career on being the community’s watchdog. At a time when local news is underreported by major news media, as a journalist, Anthony helped shine a spotlight on Inland Empire policymakers and government agencies and their policy positions on immigration, homelessness, job-creation and public safety.

Autumn E. Blackburn

Autumn E. Blackburn

Autumn Blackburn was born and raised in the 6th ward of San Bernardino. She has been one of the most resilient people I’ve ever gotten the chance to work with, even after losing both of her parents she still managed to survive and graduate high school. In 2017, she was elected as the San Bernardino Valley College Student Trustee and helped co-found Student Jibe with a group of friends, a student lead effort to help formerly incarcerated individuals navigate the college system, get help with FAFSA, and connecting them with other resources already available in San Bernardino. Autumn volunteers at the House of Hope IE and continues to be a big advocate for women’s rights through Planned Parenthood.

Berenice Villa

Berenice Villa’s roots are deep in San Bernardino. Berenice started her community involvement at Colton High School with an after school girl’s empowerment club called Girls Con Ganas. She led the initiative to pass the social host ordinance in various cities across the IE. She continued her work with Mental Health System where she formed various coalitions of families to reduce underage drinking and drug use. This community work came naturally because of Berenice’s faith. She serves as a youth leader for Youth In Action, a youth ministry at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, San Bernardino.

Charles “Silky Smooth” Harris

Charles Harris has been boxing since he was 8. He came to Project Fighting Chance in 2016. In 2017 he fought his way to the National Junior Olympics in Charleston, West Virginia. He competed and after 4 fights was crowned National Junior Olympic Champion leaving with the #1 ranking. He then went through the competition at Nationals in Salt Lake, only to be handed a very questionable decision loss in the finals leaving with the Silver. He is a very humble and respectful young man who desires to one day be a world Champ.

Destiny Muse

Destiny Muse

Destiny Muse was born in San Bernardino and raised in Rialto where she attended Frisbie Middle School and graduated from Eisenhower High School in 2009. She is currently attending Cal State San Bernardino where she will receive her Bachelors in Psychology. Destiny has been producing events for 3 years and recently launched an event company called “The Muse” which focuses on building individuals through artistic, entrepreneurial, and interpersonal growth. Destiny Muse has added a fresh environment of creative expression in downtown Rialto. Lunch Break – an art showcase was featured in the local newspaper. Since the start of Lunch Break in April, Destiny has received two awards honoring her leadership abilities and contributions to others: one from Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and one from Assemblymember Eloise Goméz Reyes.

Estefania Esparza

Estefania has volunteered with various community organizations throughout the Inland Empire. Her endless efforts have included volunteering with many non-profit organizations including Inland Congregations United for Change (ICUC), Mi Familia Vota, El Sol Educational Community Center amongst others. Throughout her college years Estefania, was very closely involved with immigration work in the community. She assisted many people with DACA applications, as well as finding other resources for undocumented immigrants. Estefania just graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology from Cal State University of San Bernardino.

Francis Chavez

Francis Chavez is a first-generation Guatemalan-American. Her family originated from Guatemala and embedded in her the value of public and community service, which has ignited in her a passion to pursue a career in the Foreign Service. In 2015, she went on to earn two bachelor degrees in Political Science and Spanish, with a minor in Business Administration from Point Loma Nazarene University (PLNU) in San Diego, California. Francis served on two humanitarian mission trips to Armenia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo where she and her team worked with the various communities in need on behalf of Point Loma Nazarene University. As a year-long international student, Francis volunteered as a teacher’s assistant in a rural school in Seville, Spain, teaching English to children, K-3rd. She now serves as the Political and Community Affairs Assistant at the Consulate of Guatemala in San Bernardino, fulfilling the needs of the local Guatemalan community.

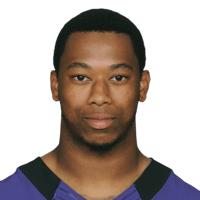

Gary Walker

Gary Walker

Gary Walker Jr. is an American football free safety who is currently a free agent. He was signed by the Baltimore Ravens as an undrafted free agent in 2013. He played college football for the University of Idaho. Gary now spends his time in the Inland Empire training and mentoring young athletes through his lifestyle brand athletic training company Get Your Mind Right.

Guadalupe Tellez

Guadalupe Tellez is18 years old and just graduated from Arroyo Valley High School. During high school she has been involved in community service, such as, phone banking for ICUC students for change. Last year she was involved in Assemblymember Reyes’ Young Legislator program. Her participation led to her advocacy for the Muscoy Sidewalks for Safety campaign. She plans on attending University of California, Merced in the Fall.

Ivan Aguayo

Ivan Aguayo began as a young man advocating for the most vulnerable in the community. His activism took him to Inland Congregations United for Change (ICUC) where he was a young trainee. Throughout his professional career, Ivan has mentored countless activists who have accepted positions in politics, community-based organizations, campaigns and elected offices. Ivan has managed local and regional campaigns and grassroots field operations with resounding success.

Izaiah Frazier

Izaiah Frazier is a 14 year old TeenPreneur, and President of the Mini Mogul Club where he teaches monthly workshops like Instagram for Business, the Cash Flow Quadrant and golf. At age 7, Izaiah founded his first company, Dollar Chores For Sale, a service business offering lawn care, recycling, document shredding, and kick scooter repair. His business story was featured in Yes We Can Newspaper. Izaiah has accomplished over 140 hours of community service, and was recognized by the California Assembly and City of Rialto for completing Shades of Blue Aeronautics Academy where he co-piloted his first Cessna flight. Izaiah’s goals are to grow his Rare Flip.biz retail company, sell his existing service business, and continue to inspire other youth to become business owners before their 20th birthday.

James Albert

James Albert has been an avid, competitive athlete in golf, basketball, and baseball. He graduated from Aquinas High School in 2009 and was awarded an athletic scholarship to California State University, Monterey Bay and competed as a dual sport, student-athlete in basketball and golf. He graduated cum laude and received his Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology in May of 2013.

He found his voice in the historic, grassroots presidential campaign of U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. He was elected to serve as a Delegate for Senator Bernie Sanders Presidential Campaign to the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. James has been actively involved in coalition building that engages high school, community, and 4-year college students to find their voice and engage them in the political process through civic education presentations and town halls in the Inland Empire.

Currently, he is appointed to the Young Leaders Advisory Council of the South Coast Air Quality Management District and serves on the boards of the San Bernardino County Young Democrats and the League of Women Voters of the San Bernardino Area.

Janneth Milian

Janneth Milian is a current undergraduate student at California State University, San Bernardino pursuing a degree in Liberal Studies with a concentration in Gender and Sexuality Studies. Milian was recently appointed as the student voting representative for the College of Education where she partners with the Dean of the College to focus on issues on food insecurity, scholarship funding, and study space availability.

Javier Hernandez

Javier Hernandez has taken direct action against anti-immigrant policies and deportations throughout the country and is a co-founder of the Inland Empire-Immigrant Youth Collective. His efforts towards improving the lives of the immigrant community started many years ago. In June 2012, Javier did a sit-in and six-day hunger strike at the Organizing for America office in Denver to bring awareness of the record-setting number of deportations in President Obama’s first term. Currently, Javier is the Director of the Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice (ICIJ), a regional coalition advancing immigrant rights in the Inland Empire.

Jennifer Xicara

Jennifer Xicara, 26 years old, Co-Founder and Program Manager of Akoma Unity Center (Akoma) which is located in San Bernardino, CA. Akoma is a Non-Profit organization that consists of programs and services that are specifically designed to meet the needs of historically excluded African American youth and communities. Jennifer is a native of the City of Rialto and also an alumnus of Eisenhower High School. In 2014, Jennifer received her Bachelors of Science in Women’s Studies and Public Policy from University of California, Riverside. Her goal is to empower marginalized and disenfranchised communities of color. Through her grass roots activism and dedication to the community, Jennifer is fulfilling her life’s work

Jessica Gunawan

Jessica Gunawan recently joined A&R Tarpaulines, Inc. team as Project Manager. She is an avid volunteer with 10 cent Meal Mission which serves to feed approximately 300 children in Tanuan, Leyte, Philippines. Also, she volunteers with Justice Speaks which is non-profit organization advocating against human sex trafficking. With her new role and active volunteering service, Gunawan’s goal is to spark hope and spread love to those in need.

John Devine

John Devine currently lives in Riverside, CA where he is a Master’s of Social Work graduate student at California State University, San Bernardino. John currently works as a Peer and Family Assistant for the Independent Living Program, a program to prepare foster youth for adulthood and to become self-sufficient, successful adults. John has worked with a number of organizations including; National Foster Youth Institute, Foster Club, Foster Youth in Action, and Foster Leaders Movement.

Jonathan Gonzalez-Montelongo

Jonathan Gonzalez-Montelongo serves as the Campus Tour and Events Coordinator at California State University, San Bernardino. He also serves on the Black and Brown Committee where he implements programs for Black And Brown young males in the Inland Empire.

Jonathan Williams

Jonathan Williams wears numerous hats as a Certified Integrative Wellness & Life Coach, Substitute Teacher, and a Mental Health practitioner. Equally, he is a skilled recording artist, trained actor, and tactful lyricist. With a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and a minor in Drama Education from Cal State University, San Bernardino he uses his knowledge to artistically heal and advocate in the name of mental health and social justice. With goals of becoming a Licensed Drama Therapist, he seeks to connect and heal the lives of others, especially other artists, leading them towards balance and wholeness.

Joseline Moran

Joseline Moran is a recent graduate from Arroyo Valley High School who was part of Assemblymember Eloise Gómez Reyes’ Inaugural Young Legislators Class. An essential part of the Young Legislators Program for the 47th Assembly District, she actively participated and provided potential legislative ideas to help shape our community. Recently, Joseline helped organized a group called SOAR IE to bring sidewalks to schools in Muscoy. Her dedication led to bring temporary safety infrastructure for the community to help get input for future grants.

Juan Villa

Juan Villa is a lifelong resident of San Bernardino. He is currently going to San Bernardino Valley College and is pursuing an AA-T in Political Science. Because of his political interest, he is a California Democratic Delegate for the 47th assembly district. In his free time, he serves as the president of La Plaza/Ramona Neighborhood Association and youth leader for the Youth In Action ministry of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church.

Lyzzeth Mendoza

Lyzzeth Mendoza has been active in immigrants’ rights and public policy advocacy for over 8 years. She has worked with Inland Congregations United for Change (ICUC) and 5 years with Inland Empire Immigrant Youth Collective and Catholic Relief Services. Lyzzeth coordinated over 15 DACA clinics with pro bono immigration attorneys and local nonprofits. Additionally, she led a group of community members in a series of advocacy meetings for policies that advanced the life of the immigrant community and tracked local legislation relevant to immigrant issues.

Malek Bendelhoum

Malek Bendelhoum was raised in Moreno Valley, California in a multicultural home with his father from Algeria and mother, an African American from Alabama. Malek received his bachelor’s degrees from University of California, Riverside in Political Science and Forensic Psychology. He has also traveled to Saudi Arabia for Islamic Studies and is a committed student to the Islamic Sciences. Currently Malek is Co-Founder at Sahaba Initiative and the Associate Director of the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California.

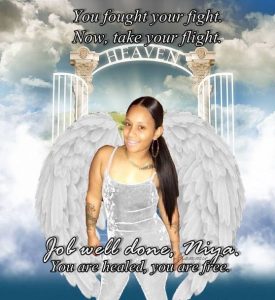

Nia Bush

Nia Bush, a San Bernardino native, graduated from Spelman College in May 2017, Magna Cum Laude, with a degree in Philosophy and a minor in Comparative Women’s Studies. Currently, Nia serves as a Volunteer Coordinator for Youth Action Project. Nia is responsible for organizing YAP’s community events and activities that help recruit and engage short and long term volunteers. Because of Nia’s efforts, over 700 homeless individuals received food and basic necessity bags.

Nicholas Akingbemi

Nicholas began his career in law enforcement working for the San Bernardino County Probation Department at the age of 21. Now at 25, Nicholas is a police officer for the UCI police department and speaks at several college and high school campuses with a focus on mending the relationship between law enforcement and the general public. Nicholas has served as an advocate, educator, and confidant in the communities of the Inland Empire. Currently, Nicholas has embarked of becoming a criminal defense Attorney for underrepresented minorities

Noah Asherbranner

Noah Asherbranner faced hardships with his health at a younger age, yet continued to persevere towards his dream in technology. Asherbranner recently graduated Grand Terrace High School (GTHS) where he served as the videographer and producer for the GTHS Girls’ Basketball team and an administrator for the community Facebook page. Noah will be attending Arizona State’s Polytechnic Campus for Robot Engineering in August.

Polet Milian

As a California State University, San Bernardino alumnae, Polet is deeply committed to supporting our students to achieve their career goals through professional advisement and college success initiatives.

Polet is a true leader to watch. She chaired the 2018 Women’s Leadership conference inviting hundreds of faculty, staff and students together to celebrate and learn how to advocate on behalf of women leaders and how to become a woman leader in their family, community and organizations. She led 50/50 day, a global awareness campaign to ensure a just and gender equitable society. Her curriculum for the day was considered so exceptional, that CSUSB was selected as one of 25 programs that were highlighted globally. Polet serves on the African American Student Recruitment and Retention Task Force at CSUSB, established to recommend strategies to strengthen African American enrollment, student success, and graduation rates. She brings an equity-minded approach to all her work and understands the importance of promoting diversity, equity and inclusion to ensure student success. Polet is always willing to give of her time and has garnered a great amount of respect for her commitment to the work of the task force.

Sadie Albers

Sadie Albers is currently assigned as the San Bernardino Police Department, Northern District Community Engagement Specialist. Ms. Albers is primarily responsible for developing and implementing communications and community engagement strategies, in order to enhance the department’s presence within the city. Sadie was a recent recipient of the “Shining Star-Emerging Leader” Award, presented by the Orange County Chapter of the Public Relations Society of America.

Yassi Kavezade

Yassi Kavezade was born and raised in southern California her whole life and is the eldest daughter of Iranian immigrants. She moved to the Inland region to complete her studies at UC Riverside majoring in Psychology with a Minor in Environmental Sciences. Yassi currently works as an organizing representative for My Generation. She and her team fight to build solutions for cleaner air and power that is rooted in justice across the district.

Who: Assemblymember Eloise Gómez Reyes recognizing the top 30 young adults under the age of 30 for their achievements in community activism, business, health, education, art and social entrepreneurship.

What: 30 Under 30 Award Ceremony & Art Showcase

Where: Court Street Square | 349 N E St, San Bernardino, CA 92401

When: Saturday, July 28, 2018 from 7:30pm – 9:30pm

RSVP: Go to the link https://www.eventbrite.com/e/30-under-30-award-ceremony-art-showcase-tickets-47195413753 or call District Representative Daniel Peeden at (909) 381-3238

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence