By Tanu Henry | California Black Media

After Carl Maryland retired in 2009, he started playing for a team in the Sacramento Golden Seniors Softball Club league.

“Mostly to stay active and fit,” the 78-year-old says, but he enjoyed hanging out and shooting the breeze with his teammates, too.

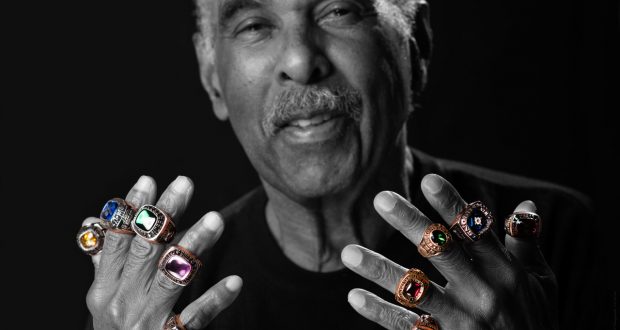

During his seven-year run, playing in the league, Maryland’s team won 10 championship rings.

“If you love the game, you got to stay with it,” says Maryland.

Then, two years ago, he fell ill. His doctor advised him to take some time off from playing. In April of this year, when it was time to go back, he wasn’t well enough to get back on the field.

Maryland has now moved into his son Robert’s home in Sacramento. Occasionally, they go out to the batting cage and play catch together.

The younger Maryland is freelance photographer and father of two. He loves hanging out with his dad, he says. And although the senior Maryland is independent most of the time, caring for him while balancing all of his other obligations at home and work can be challenging.

“He doesn’t drive anymore,” Robert says. “It would be good if he could go out at anytime and hang out with his buddies. He misses that.”

In California, caring for aging parents can be difficult for middle income families like the Marylands. There are few resources they can access for information or money to pay for medical bills, at-home care, or other needs. The state provides assistance for home aides and transportation for low-income families. And most aging Californians who are wealthy can afford to move into plush nursing homes or senior communities – an unaffordable option for average families – where there are people on staff to assist them.

Expecting California’s aging population to balloon by about 4 million to 8.6 million people by 2030, Gov. Newsom is taking steps to meet the needs of families like the Marylands.

In June, the governor issued an executive order, asking the Secretary of the Health and Human Services (HHS) to set up a cabinet-level “Workgroup for Aging” to advise the Secretary on “developing” a Master Plan on policy and programs.

Gov. Newsom expects the committee to complete and deliver the Master Plan by October 2020.

To support the workgroup, Ghaly announced the creation of an advisory committee comprised of Californians from various backgrounds who have some expertise on aging, including former Assemblymember Cheryl Brown (D-San Bernardino). Brown was chair of the Assembly Committee on Aging and Long Term Care during her tenure in the legislature.

For Brown, working to solve problems aging adults and their caregivers face is fulfilling. Since she was about 14 years old, Brown says she remembers being a caretaker for aging adults in her family.

“I never thought twice about it,” says Brown. “That’s what we did. Families used to have that intergenerational support. It brought us closer together. It made us stronger.”

That’s why, Brown says, when she was a member of the state legislature – a Democrat representing a district covering parts of the Inland Empire from 2012 to 2016 – she authored legislation that would have required the state to set up a task force on caregivers for aging adults. The bill passed in the full Assembly and state Senate. But when it landed on then-Gov. Jerry Brown’s desk, he vetoed the legislation, letting her know there was not a need at the time for the team she was proposing.

“Of course, I disagreed,”said Brown. “ Californians provide an estimated $47 billion a year in unpaid labor taking care of their families and every day in California, 1,000 people turn 65. Long-term care costs are increasing.”

Instead of re-introducing the bill or authoring a similar one, Brown wrote a resolution that pointed out the need for the task force on caregiving for the aging. It passed in both the Assembly and Senate.

Now, with her new appointment to the advisory committee, Brown says she’s ready the to join other Californians on the board to influence statewide policy on aging adults

“Our collective charge is to develop a roadmap that envisions a future where all Californians, regardless of race, economic status or level of support, can grow old safely, with dignity and independence,” wrote Marko Mijic, a Deputy Secretary at the HHS in an email to the new committee members.

Gov. Newsom, who has first-hand caregiver experience from taking care of his dad before his death in 2018, announced the Master Plan committee in his State of the State speech in January. The governor’s father, William Newsom, was a former Appeals Court Judge who suffered from dementia.

The governor said the plan must be “person-centered” and address issues like isolation, transportation, the nursing shortage and the increasing demand for in-home supportive services.”

By 2030, the Public Policy Institute of California estimates about 1 million aging adults in the state will need some assistance to take care of themselves. The population of seniors who will need nursing home care is expected to grow as well. California is also one of 14 states that has a poverty rate of more than 10 percent among the 65-and-older population, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Accurately counting California’s aging population in next year’s Census will be a challenge as more and more aging adults fall in to poverty, become isolated from family and social networks, and continue to lack access to the internet. The 2020 Census will be the first to be primarily conducted online.

Brown says it is important for California to get ahead of the challenges coming.

“How do we create a one-stop shop?,” asks Brown. “What can we do to assist middle income families? Then, there is the sandwich generation – those working Californians with both young children and aging parents. How can we help them to help their loved ones?”

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence