High profile acts of violence against African American men have been recorded and broadcast widely in recent weeks, including the death of a Minneapolis man, George Floyd.

USC experts share their expertise on how racial violence and recordings of these episodes intersect with history, law and health outcomes in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even Ivy League degrees don’t protect African Americans

“A deathly disregard for black lives is the blood red thread stitched into the very fabric of our nation. As a historian of the black past, I am all too familiar with the litany of torture, lynchings, rapes, false imprisonment, peonage, convict leasing, mass incarceration and medical apartheid from 1619 to 2020. As the mother of two black men, I live in fear of their injury, arrest or demise at the hands of a capricious passerby, contemptuous police officers, or uncaring physicians. The casual refusal by every level of government of black men and women’s right to breathe, bird or just be in their own bed or kitchen or car is soul crushing.

“My three Ivy League degrees do not provide me with any more PPE against racism and white supremacy than Christian Cooper’s Harvard B.A. did in Central Park.”

Francille Rusan Wilson is an associate professor of American Studies and Ethnicity, History, Gender & Sexuality Studies at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and the immediate past president of the Association of Black Women Historians.

Contact: frwilson@usc.edu

Police racial violence should be every American’s concern

“The core concern of the #BlackLivesMatter movement from its very inception has been the indifference or outright hostility of state actors like police officers and prosecutors to the value of black lives. Unlike private individuals, when state actors attack and disrespect citizens, they implicate all Americans because they act in our name and on our behalf. When a police officer is killed in the line of duty, law enforcement representatives have been quick to assert that an attack on an officer is an attack on America.

“By the same token, when an officer unjustifiably brutalizes or kills a black person, that’s not just a private citizen attacking another private citizen, that’s America assailing that black man, woman, or child. Cops don’t get to be equated with America when they are victims but then reduced to ordinary private citizens when they are victimizers.”

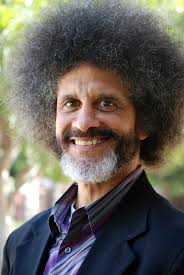

Jody Armour studies the intersection of race and legal decision making as well as torts and tort reform movements as the Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at USC Gould School of Law.

Contact: armour@law.usc.edu or (213) 740-2559

The loop of videos takes a toll on kids

“My work has shown that when adolescents of color watch viral videos of police racial violence online, that exposure is associated with increased depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress symptoms.”

“During the coronavirus pandemic, students’ classes and social lives are almost entirely online. Previously, young people had a traditional setting where they could find in-person social support if they are feeling overwhelmed by what they are seeing in digital spaces and not ready to share with members of their family. Now, young people may not have that buffer against poor mental health outcomes.

“We can’t underestimate the importance of touch and the ability to see the physical cues that someone is in distress. There is power in the in-person connections people make that we haven’t yet been able to replicate in the most common digital contexts.”

Brendesha Tynes is an associate professor of education and psychology at the USC Rossier School of Education. Her recent research has examined the association between exposure to violent racial videos online and mental health in African American and Latinx adolescents.

Contact: btynes@usc.edu

Images of racial violence can be exploitative

“To me, airing the tragic footage on TV, in auto-play videos on websites and social media is no longer serving its social justice purpose, and is now simply exploitative.

“Likening the fatal footage of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd to lynching photographs invites us to treat them more thoughtfully. We can respect these images. We can handle them with care.

“It’s time to revisit the relationship we have with cellphone videos and social media. Trauma is compounding for many African Americans, who are already fighting a separate, disproportionate battle against COVID-19.”

Allissa Richardson is an assistant professor of communication and journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and the author of the book, Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones and the New Protest #Journalism.

Contact: allissar@usc.edu or (213) 740-9700

Stress from racism leads to poor health outcomes

“For African Americans, the most stressful part of experiencing discrimination is not knowing when it’s going to happen next. That’s the key. Widely-circulated videos of violence against black people add to this anticipatory anxiety.

“This has implications for African Americans’ health outcomes during the coronavirus pandemic. Chronic stress can alter the expression of genes that are involved in both the antiviral and the inflammatory response. Chronic inflammation is involved in a number of health conditions including autoimmune conditions, diabetes and obesity. There have been several studies showing higher inflammatory markers in African Americans, so it’s not surprising that this group is disproportionately impacted and dying at higher rates from COVID-19.”

April Thames is an associate professor of psychology and psychiatry at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. Her research has focused on how racist experiences increase inflammation in African American individuals, raising their risk of chronic illness.

Contact: thames@usc.edu

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence