By Charles Ellison, b|e note

At some point, the leftovers conversation about Black male voters was bound to catch up with us. A week of apoplexy over the self-absorbed political leanings of Big Chain rap icons Ice Cube then 50 Cent led to widespread social media and pop Black discourse condemnation about the electoral behavior of Black men overall. Once again, an entire classroom of the well-behaved was punished for the “spit balling” antics of the very few in the back of the classroom.

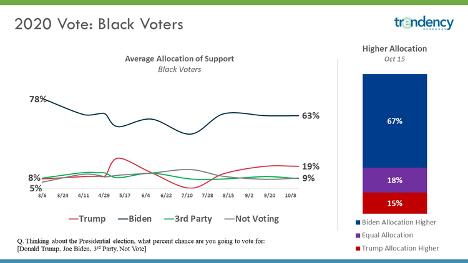

Many people, particularly those in the Black academic, political and media space, carried on a careless, angry exchange since 2016 focused on the contemptible Black male voter. According to exit polls, a small, yet noticeable, collection of activated Black male voters (13 percent) supported Donald Trump for president. That led to a bizarre, irresponsible and very knee-jerkish rejection of Black men voters as a whole and conveniently aligned with a Trump Era-timed celebration of Black women voters as the only known hope to restore any semblance of Black political power. Ignored was the fact that the overwhelming majority of Black men voting had sense enough to support Hillary Clinton, 82 percent. Still, Black women voters scrambled to save the world that ill-fated night four years ago (I wrote the headline). But, Black male voters, on the other hand, felt wiped from the electoral map after 2016: disgraced, dishonored and alienated even as the majority of them did the right thing.

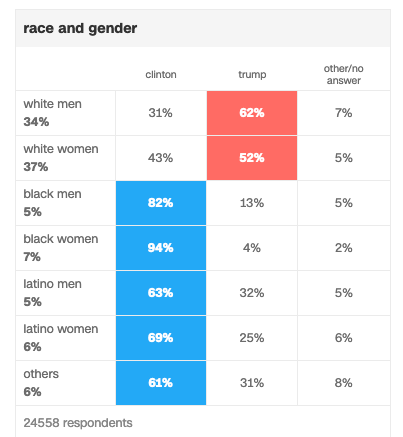

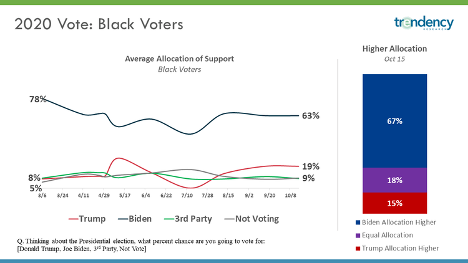

Those sentiments had consequences, particularly for the next Generation Z of young Black men who should have spent much of the past several years looking forward to participating in their first election. Instead, they’ve been hearing commentary on their electoral worthlessness. Their presence was mad invisible in key election cycles since then. Now, as 2020 looms, the political world needs them – but, just how psychologically battered and bruised are they? Stressed Democrats looking for a convincing leg-room margin for Joe Biden-Kamala Harris against incumbent Donald Trump-Mike Pence are now begging for Black male votes. Democratic Party leaders fret privately and publicly that much of the Black male electorate has tapped out. But, where was all this clamoring for brothers over the past several years? Much of the sudden focus seems a day late and a dollar short. As a result, we’re seeing troubling pro-Trump and “not voting” Black voter numbers like these …

This is compared to overall Black voter breakdowns in 2016 …

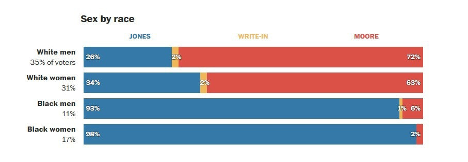

During the Alabama U.S. Senate race concerns arose that the Black male vote either did not exist or would not show up – because of, once again, that knuckleheaded 13 percent in the back of the classroom. Yet, the Black male vote did show up. It certainly took a back seat to Black female voter performance in terms of pure numbers, representing 11 percent of the overall state electorate while the “sister vote” represented 18 percent of it. But, Black male presence at the polls was equally significant and decisive.

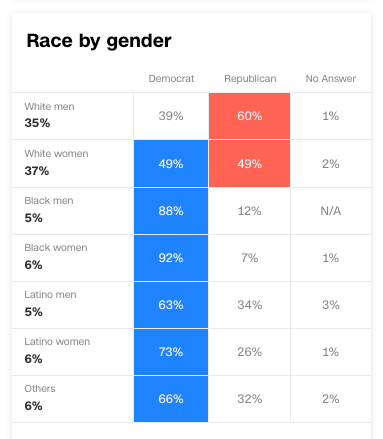

In 2018, Black male voters once again, voted mostly in their community’s best interest: 88 percent voting for Democrats to retake the House versue 12 percent voting for Republicans. Granted, that didn’t match the support shown by Black women (92 percent), but it was still a significant majority …

It’s a delicate conversation. Observers tiptoe gently around the subject out of fear that it will be misinterpreted as an act of political chauvinism. It’s a cautious assessment, but a real and valid one: no conversation on Black vote behavior should be divisive, least of all from the perspective of Black people engaged on the topic. Any analysis should be thoughtful and respectful, with great care not to diminish the verypowerful, essential and decisive role Black women played in that race and many others before it — as they will continue to do.

Indeed, when it comes to Black voting trends and Black political efficacy, Black women do indeed lead. That has been the case for quite some time.

However, any discussion on Black voter behavior and patterns should be holistic and unifying; in the case of Alabama (U.S. Senate) and Virginia (Governor) in 2017 and the 2018 Congressional midterms, there is a sense that mainstream discussion on that Black vote has not been as complete as it should be. It would be difficult to ponder Black Electorate effectiveness if the zeitgeist and Democratic Party planning focused disproportionately on one half of the equation. No Black voting bloc — no voting bloc for that matter — is totally effective without coordination of all parts. For example, registered Black African and Caribbean migrant communities, which are mainly clustered alongside Black American communities, must be taken into account when mobilizing modern Black voting blocs. The same must, naturally, occur with the Black vote in its entirety; there is no whole or pluralistic Black vote without both Black women and men factored in.

While the commentary on Black female voter power is welcome, aspects of it are being presented by mainstream media discourse as something that existed alone, by itself, in the context of overall Black voter participation.

Black thought leaders should have approached and assessed that conversation with caution. Many did not … and are still getting trapped in it.

Both Black women and men have experienced brutal oppression over several hundred years, with white supremacist male-dominated constructs also placing great emphasis on the emasculation and destruction of Black men. Is the exclusion of mainstream media conversation on Black male voter presence and effectiveness in these election cycles deliberate? What we do know is that mainstream media institutions have long been extensions of white supremacist thought and action – and that same thought and action puts heavy focus on eliminating Black men.

Back to Alabama: Black male voters were not as numerically superior (11 percent) as Black female voters (18 percent). However, with all ballots counted, Black male presence was double digits and support for Democratic nominee and now Senator Doug Jones was 93 percent. That’s a sharp 5 percentage points less than Black women’s support for Jones, but it is nevertheless impressive and well above the 90th percentile range. It should have been recognized and factored in for future planning on Black voter mobilization efforts. That should have been a story.

Interestingly enough, during the 2008 election, Black Alabama male voter support for then-Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama actually surpassed Black Alabama female voter support for Obama by 4 percentage points — 100 percent of Black men voters in Alabama supported Obama compared to 96 percent of Black women. Still, Black Alabama men only accounted for 11 percent of the state electorate.

In 2012, that turnout dropped by 1 percentage point. But, they voted to re-elect President Obama at 96 percent compared to Black women voters in the state at 95 percent.

Black male voters have not yet been forgiven (by some) for increased support of Democratic nominee Bernie Sanders during the caustic 2016 Democratic primary and what was considered, later on in the general, an unusually higher number of Black male voters who voted for Republican candidate Donald Trump. Observers have pointed to sexism as the culprit influencing the decisions of some Black male voters.

In contrast, Black women voters were fairly focused and unified in their opposition to Trump in 2016. While accounting for 7 percent of the overall U.S. electorate, they voted 94 percent for Clinton versus only 4 percent for Trump and 2 percent “other.”

Still, 2016 aside, Black male voters prominently figure in any race without question. Commentators, particularly those in the Black thought leadership space, would be wise not to completely discount or casually dismiss the Black male voter, especially at a time when conversation must encourage greater turnout from them in 2020. Yet, they still are. Is it too late? With Black male voters so invisible from the conversation during all those key moments of Black electoral enthusiasm and reflection, there was always a high risk of psycho-social alienation that would show itself in reduced Black male voter turnout in future elections. At this stage, Black people will need all the voter turnout they can get – from both Black women and Black men. You can’t half-step a Black vote.

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence