By Christina Laster | NAACP Education Chair | #BlackEdChat

Black teacher presence in the classroom may be showing some signs of progress, but not nearly enough

EMPIRE NEWS NETWORK (ENN)— The historic Brown vs Board of Education (1954) case not only “desegregated” the nation’s public schools, but it also opened up desegregation of lunch counters in North Carolina, public transportation in Alabama, and public spaces across the entire nation.

Still, desegregation had its costs – especially within the public education system. While the doors to Whites-only schools were opening for Black students, the doors to classrooms and offices were being closed to Black teachers and principals.

In the period immediately following Brown, for example, then number of Black principals in Alabama decreased from 210 to 57. In Virginia that number plummeted from 170 to 16. Recent studies show that, currently, only 20 percent of principals across the country are non-White, and of those only 10 percent are Black.

Black teachers didn’t fare much better back then and, unfortunately, they’re not faring much better now.

In segregated schools, Black teachers served as more than gatekeepers to information and degrees. They were culturally relevant advocates, allies, friends, and family. They were sharing a common purpose in prevalent conditions of struggle, using shared cultural knowledge and forms of interaction to navigate. In White schools, Black teachers were seen as invaders and access was only granted to those that could show the highest levels of proficiency in the performance of “Whiteness.” Most frequently, these measures of performance took the form of graduate school programs, degrees and certifications that Black educators were unable to access or not allowed to complete.

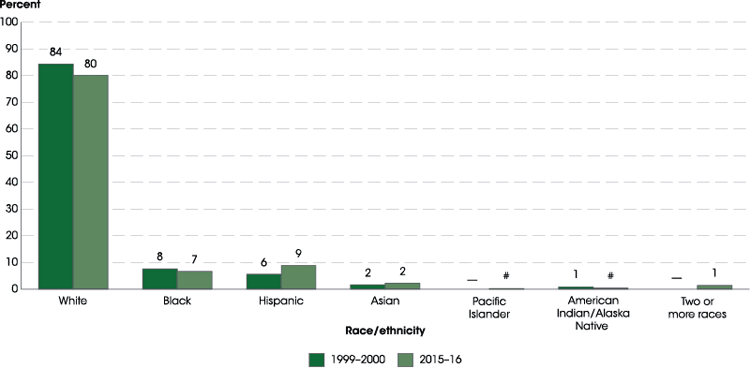

Today, while approximately half of students in the public school system are Black, Latino, Indigenous, or otherwise not White, over 80 percent of teachers identify as Caucasian. Furthermore, only 7 percent of public teachers are Black while 16 percent of the student population is Black. Black teacher presence in the classroom may be showing some signs of progress, but it’s not proportional to the overall national Black student population and it’s not growing at a rate that’s fast enough to keep up with current demographic trends.

Lack of access to certification, discrimination on the part of many White administrators, and a lack of culturally relevant representatives to bridge the gap between students and teachers are among the primary reasons Black teachers are having trouble accessing Black classrooms. Non-traditional and tailored public schools, however, have become a unique bubble of protection for Black educators and administrators to reenter the public education system. The results have been promising.

Non-traditional, non-profit public schools are bucking the trend of lost Black educators.

A recent study examining non-profit public schools in North Carolina showed that while the proportion of Black students in those non-traditional and traditional public schools are similar, the non-traditional alternatives have approximately 35 percent more Black teachers. Further, Black students in tailored public schools are 50 percent more likely to have at least one Black teacher than their peers attending traditional public schools.

Having Black teachers in classrooms with Black students is paying off.

Studies, such as one recently from Johns Hopkins University, have shown that Black elementary school students perform better in math and reading when they have a Black teacher. Just one Black teacher “reduced their probability of dropping out by 29 percent for low-income black students – and 39 percent for very low-income Black boys.” They are more likely to find themselves placed in gifted programs, and Black students are also more likely to graduate from high school and enroll in college with exposure to just one Black teacher in their schools.

Reinserting Black representation into the classroom also serves to protect students form the harsh and asymmetrical punishments they experience, on average, at the hands of mostly White instructors. That’s not saying or proving all White teachers are bad for Black students; but there are major disparities needing more analysis, policy redress and improvement. But, in the meantime, we do see success when Black students are either with Black teachers or interfacing in the same spaces with them: they are less likely to face expulsion, suspension or detention. They are also less likely to face the low expectations often set for them by many White teachers stemming from implicit and explicit bias.

This can be fixed. There is a way to achieve balance, proportionality and, ultimately, high-achievement outcomes by recognizing the need for more Black teachers. By offering Black students the types of teachers they can look up to as culturally relevant representatives, non-profit public schools – such as the highly successful network of Learn4Life personalized or tailored learning public schools in California – are not only undoing the damage left in the wake of the desegregation movement, but they are rebuilding the bonds of confidence and support that reach full equity in society as a whole.

Rather than taking resources away from public schools, they are actually expanding the original spirit of public education while restoring hope to non-traditional students. These uniquely designed and transformative educational institutions are providing a vital space of universal inclusion for teachers and principals, as well. And they are better serving Black students in the process.

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence