African American cowgirls do exist.

Each year hundreds of Black women travel across the United States to compete in ladies steer wrestling, breakaway roping, bull riding, barrel racing, and other rodeo competitions — many while holding down full-time jobs.

The rise of Black women in the rodeo circuit is largely due to the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo (BPIR), the nation’s only African American touring rodeo, which was founded by Lu Vason in Denver, Colorado, in 1984.

Named in honor of Willie M. ‘Bill’ Pickett, BPIR was an African American cowboy, actor, and ProRodeo Hall of Fame inductee. He invented the bulldogging technique — a rodeo event where a rider wrestles a steer to the ground by grabbing its horns.

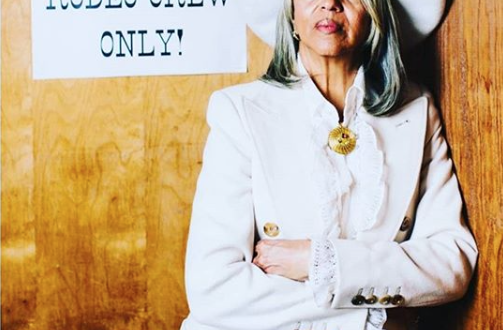

Today, BPIR has a woman at the helm and is run by a majority female leadership team.

Since taking the reins in 2015, Vason’s wife Valeria Howard-Cunningham has used her position as CEO to promote women to leadership roles, effectively creating the first successful touring rodeo led by a Black woman.

Although 2020 has been a challenging rodeo year with COVID-19 forcing the cancelation of the competition season, Cunningham is confident that she and her team will continue to drive the movement forward.

“Being CEO was an opportunity where I could get women involved to show that women can run a rodeo operation just as effective or more effective as men,” Cunningham said. “That was important to me. A woman has to do 10 times more than a counterpart to show they are capable of doing certain things.”

Women have been involved in the rodeo world at various levels for decades. However, they have been mostly underrepresented, said Krishaun Adair of Point Blank, Texas, who has been competing in rodeo since she was five years old.

“I did not realize we were like unicorns. I didn’t realize there was a lack of or underrepresentation of Black cowgirls. I grew up looking at Black cowgirls, that’s who I wanted to be. They were my role models. Then I realized how small of a group and how precious we are. People had never seen it before, never heard of it before. Their image of a cowboy or a cowgirl looks nothing like me.”

When Adair and her friend Azja Bryant travel to competitions with horses in tow, people stop and stare, she told Zenger.

“We would stop at different gas stations, and you know, people would either look at you a little funny or [for] some people it was total fascination like they just couldn’t believe,” said Bryant. “I like to be able to perform to the best of my ability, to go out and be a positive role model to others, so I can show other people, ‘Hey there are Black cowgirls out here.’”

Adair said she admires BPIR because it creates a platform for Black cowboys and cowgirls.

“Bill Pickett [represents cowgirls and cowboys] on a level so that we don’t seem inferior or not as good,” said Adair. “I want to be seen; I don’t want to be isolated. We rodeo, we just so happen to be Black.”

Vason created BPIR as a place for African Americans to hone their rodeo skills, showcase their talents, and educate the community about Pickett.

The idea came after he attended Cheyenne Frontier Days, an outdoor rodeo and western celebration in the United States, held annually since 1897 in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Cunningham told Zenger that he did not see Black cowboys or cowgirls in the rodeo despite knowing there were thousands in the United States.

Now, BPIR has surpassed the model of being just a rodeo — it’s a community that brings people together from across the country.

“Bill Pickett is all African American,” Cunningham said. “It gives African Americans the opportunity to display skills and develop skills and not be treated unfairly. People invited to participate in the rodeo know it’s a safe zone.”

Rodeo in the United States is not just fun; it is big business. According to ranch services company Western Ranches, more than 600 rodeos nationwide are sanctioned by the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association, and in 2015 rodeo prize money surpassed $46 million. Contestants have the opportunity to win hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money in just a few days.

But sponsors and prize money do not come easily for Black rodeos.

“Because we are an African American rodeo association, the biggest challenge has been and continues to be obtaining the level of sponsorship of other rodeos,” said Cunningham.

“Companies don’t want to invest. With the National Finals Rodeo (NFR), millions can be put up for added money at their finals. We sell out all of our venues across the U.S., and we don’t get the same level of sponsorship participation. It’s the biggest struggle we have, but we don’t let that hold us back.”

African American cowboys accounted for up to 25% of workers in the cattle industry in American West, although their images were primarily excluded from popular culture. And while Black cowboys and cowgirls are common in places like Texas and Oklahoma, Cunningham said it is shocking how little is known about them in other parts of the country.

With COVID-19 causing the slowdown of rodeo competition across the country, BPIR is focusing not only on gaining sponsors but on its mission of education and getting more young people involved in the sport.

Cunningham said the Bill Pickett circuit rodeo tour introduces Black cowboys and cowgirls to children across the country and provides education about African American participation in the development of the western United States.

“Seeing kids from different communities that have never seen a Black cowboy and never seen a Black cowgirl, that’s worth more than money could ever buy,” said Cunningham. “History books don’t teach certain things. What Bill Pickett rodeo has done is to bring history alive to educate them.”

Cunningham told Zenger that parents attending and learning about BPIR for the first time often want to know where their children can learn to ride a horse and learn more about cowboys and cowgirls, which passes on the interest to a new generation.

Oklahoma native and steer undecorating champion, Carolyn Carter, began competing in 1982. Now, she has four generations of family involvement in rodeo, including a grandson and great-grandson, who are both two years old.

According to Carter, new generations of Black cowboys and cowgirls have advantages her generation did not have, such as access to parents and grandparents who know how to train horses and gained exposure to Black rodeo competitions at an early age.

“They are learning at an earlier age how to do what we’ve been doing all of these years,” said Carter. “It’s a lifestyle.”

Kalyn Womack contributed to this report.

(Edited by Rebecca Bird and Mara Welty)

The post Female CEO Steers Black Rodeo Movement appeared first on Zenger News.

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence