By Charles Ellison, the b|e note

Although housing insecurity affected communities of color long before COVID-19, the current pandemic continues to exacerbate inequalities. As early as April 2020, 32 percent of Black adults and 41 percent of Latinx adults experienced job loss due to the pandemic, compared with only 24 percent of white adults.

Black and Latina women have seen the largest drop in their employment-to-population ratios since February, with Black women in particular seeing jobs come back at a rate that is 1 1/2 times slower than that of white women. Although all racial and ethnic groups have faced record unemployment, the Black-white unemployment gap has persisted throughout the pandemic.

For Asian Americans—who have been particularly targeted by racist responses to the coronavirus crisis—unemployment rates have soared to 11 percent in July, compared with 3 percent during the previous year, and they remain historically high as the pandemic continues.

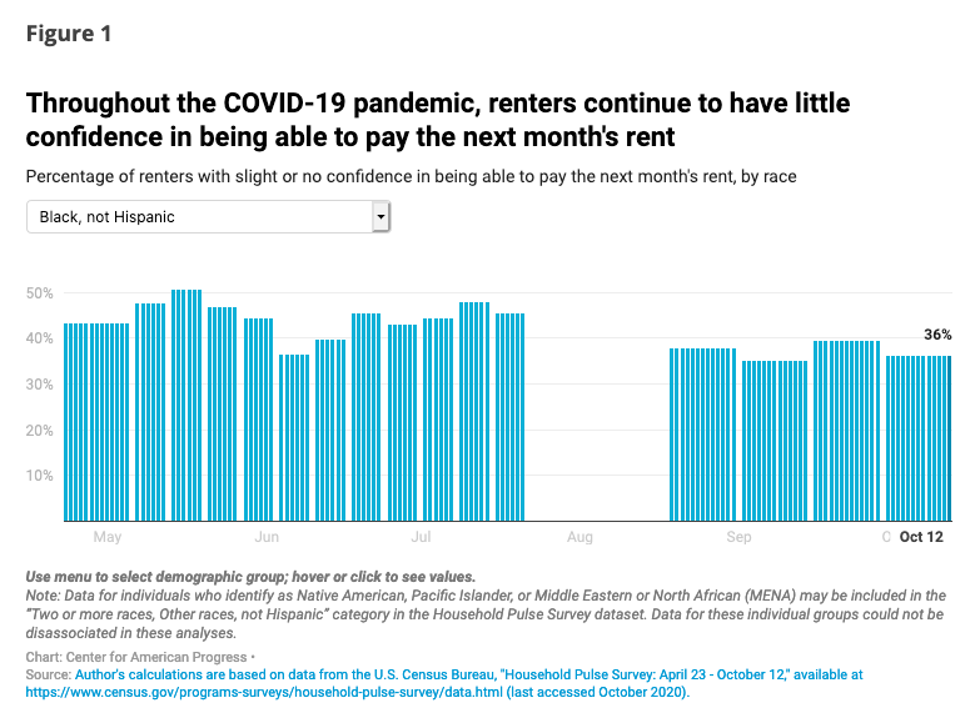

Lost and reduced income has worsened already difficult situations for many. During the pandemic, renters of color have reported less overall confidence in being able to pay their next month’s rent and have reported not having paid the previous month’s rent on time at disproportionately higher rates than their white counterparts. (see Figures 1 and 2)

With communities of color also navigating the collective pain of higher rates of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, they must face additional medical and funeral costs in addition to potential lost employer-sponsored health insurance and reduced household income due to unemployment—or worse, the loss of an income-earner’s life.

“This Scary Statistic Predicts Growing US Political Violence — Whatever Happens On Election Day” Read MORE …

“The tendency is to blame Trump, but I don’t really agree with that,” Peter Turchin, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Connecticut who studies the forces that drive political instability, told BuzzFeed News. “Trump is really not the deep structural cause.”

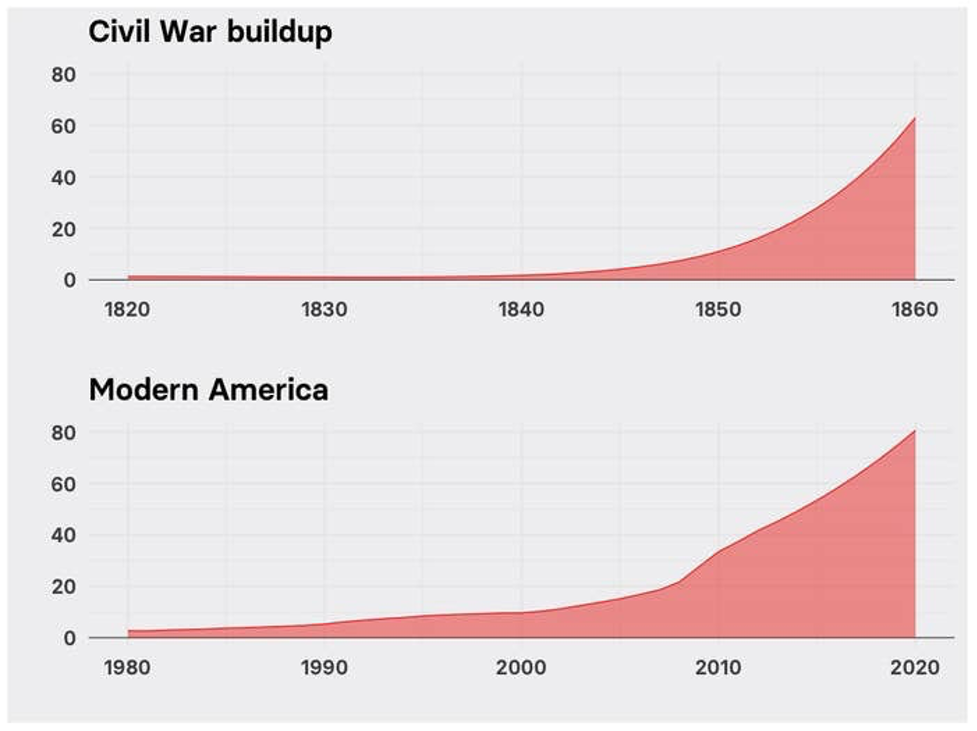

The most dangerous element in the mix, argue Turchin and George Mason University sociologist Jack Goldstone, is the corrosive effect of inequality on society. They believe they have a model that explains how inequality escalates and leads to political instability: Worsened by elites who monopolize economic gains, narrow the path to social mobility, and resist taxation, inequality ends up undermining state institutions while fomenting distrust and resentment.

Building on Goldstone’s work showing that revolutions tend to follow periods of population growth and urbanization, Turchin has developed a statistic called the political stress indicator, or PSI. It incorporates measures of wage stagnation, national debt, competition between elites, distrust in government, urbanization, and the age structure of the population.

Turchin raised warning signs of a coming storm a decade ago, predicting that instability would peak in the years around 2020. “In the United States, we have stagnating or declining real wages, a growing gap between rich and poor, overproduction of young graduates with advanced degrees, and exploding public debt,” he wrote, in a letter to the journal Nature. “Historically, such developments have served as leading indicators of looming political instability.”

“Black, Hispanic, and Young Workers Have Been Left Behind by Policymakers, But Will They Vote?” Read MORE …

Black voters have faced a 150-year struggle against voter intimidation and suppression tactics and the multilayered legacies of slavery. Black Americans are also disproportionately disenfranchised by state laws that ban convicted felons from voting—even, in some states, after they have served their full sentence. Given the U.S.’s high incarceration rate and systemic racism in the criminal justice system, this is just one more way the Black vote is suppressed.

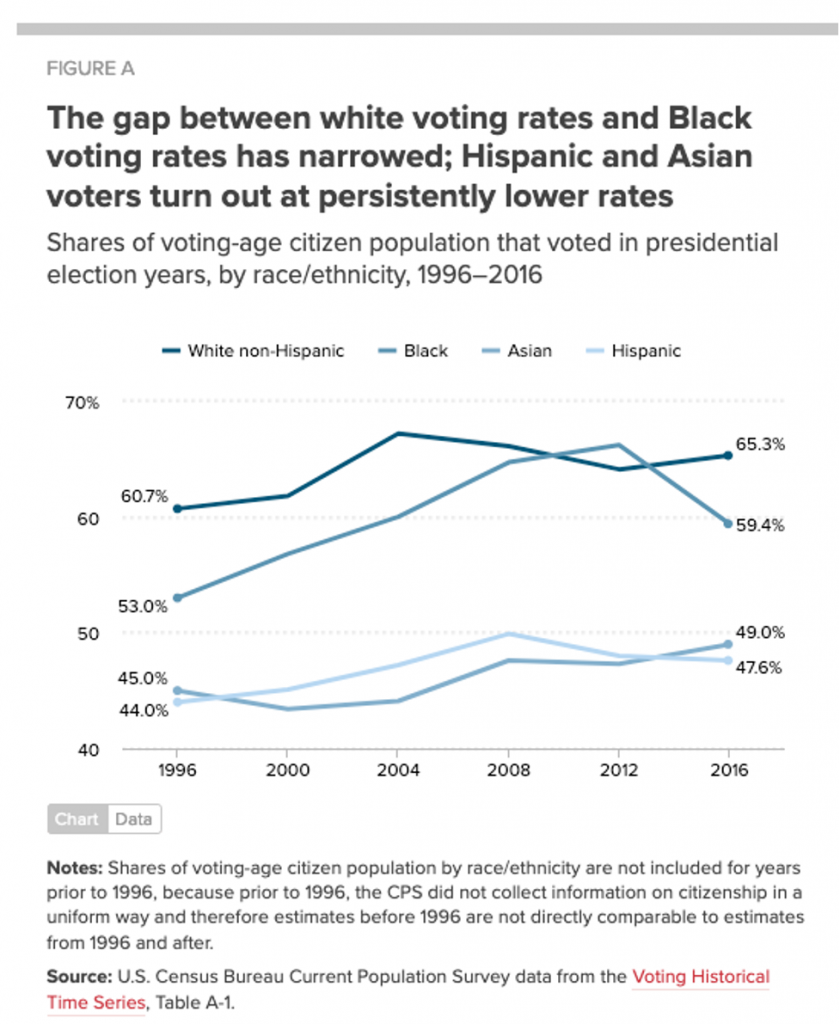

Black voter registration and participation rose after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; while Black voting rates would continue to lag behind white voting rates, the gap had narrowed significantly—particularly in the South. In 2008, the gap essentially closed, and in 2012, Black voting rates exceeded white voting rates (Figure A). However, Black voting rates dipped below white voting rates in the 2016 presidential election, asreports of voter suppression and intimidation increased relative to previous elections.

Hispanic voter turnout has been persistently lower than both Black and white voter turnout: In the 2016 presidential election, Hispanic turnout was reported by the Census Bureau at 47.6%, compared with 65.3% for non-Hispanic white voters and 59.4% for Black voters (Figure A). The reasons for low Hispanic turnout are not necessarily easy to determine and often get told one story at a time. Like Black voters, Hispanic voters have been hampered by voter suppression efforts and face disproportionate disenfranchisement due to felony convictions. Many face language barriers. The Hispanic population is also much younger (with a median age of 30 in 2018) than the white population (with a median age of 44)—and, as discussed below, younger adults are less likely to vote.1

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence