With 2020 unfolding as a year of reckoning for institutional racism, the Juneteenth holiday rises to new significance. President Donald Trump has rescheduled for this weekend a campaign rally originally set for June 19 in Tulsa, where a century ago, hundreds of Black Americans were killed and thousands were injured in a massacre that wiped out Black Wall Street. The president plans to accept the Republican nomination in Jacksonville on Aug. 27, which is the 60th anniversary of an attack on Black protesters in that city known as “Ax Handle Saturday.” USC experts discuss the significance of Juneteenth, a holiday on June 19 meant to celebrate the end of slavery in America.

The work that must be done

“What is the meaning of freedom? What are the contours of freedom and how is it an illusion? As a historian of anti-colonialism, Islam, and the Black freedom struggle, my research examines a number of mechanisms that Black people across the African diaspora have successfully used to challenge white supremacy including religion, protest, and legal and legislative mechanisms.

“In recent weeks, protesters have taken to the streets to demand justice for the victims of police violence and to insist on institutional change. On Friday, African Americans will celebrate Juneteenth, the commemoration of the official end of chattel slavery 2 ½ years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Ongoing protests make this Juneteenth significant and this year presents an opportunity to reflect on the notion of freedom and the work that must be done to sustain it.”

Alaina Morgan is assistant professor of history at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. Trained as a historian of the African Diaspora, Morgan’s research focuses on the historic utility of religion, in particular Islam, in racial liberation and anti-colonial movements of the mid- to late-20th century Atlantic world.

Contact: alainamo@usc.edu

Why was the rally originally set for Juneteenth?

“President Trump has chosen Tulsa, site of a terrible racial cleansing of African Americans from the early 20th century’s Black Wall Street to carry his message of bigotry and xenophobia to his voter base — and had originally chosen Juneteenth, the date on which African Americans in Texas celebrated emancipation from slavery.

“If he did so knowingly, it demonstrates breathtaking cynicism; if unknowingly, breathtaking historical ignorance.”

Ariela Gross is a professor of law and history at the USC Gould School of Law. Her research focuses on race and slavery in the United States and she is the author, with Alejandro de la Fuente of Harvard University, of Becoming Free, Becoming Black: Race, Freedom, and Law in Cuba, Virginia, and Louisiana.

Contact: agross@law.usc.edu

Struggle for freedom continues

“Juneteenth is an important remembrance and celebration of Black resistance and struggles for freedom and liberation. In the United States and elsewhere, Black people and others come together to commemorate the ancestors and social movements that upended slavery and who after its abolishment struggled against new forms and systems of racial violence, death, and injustice. It is a demonstration of Black joy; a celebration of Black family, community, and networks of kinship; and an altar to honor the people of past, present, and future whose sacrifices and resilience help mobilize and sustain us and raise our consciousness.

“What is ultimately important to recognize about Juneteenth is that it is not a celebration of the ‘freeing’ of Black people, but rather of Black people’s agency in rejecting and resisting dehumanization and terror. We were not freed. We have constantly struggled to free and liberate ourselves and others.”

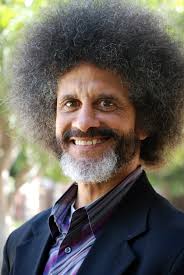

Robeson Taj Frazier is an associate professor of communication at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, and director of the Institute for Diversity and Empowerment at Annenberg (IDEA). He is a cultural historian who explores the arts, political and expressive cultures of the people of the African Diaspora in the United States and elsewhere.

Contact: rfrazier@usc.edu

The irony of Juneteenth as a celebration of freedom

“Juneteenth is set aside to celebrate freedom. The irony is that it marks a time more than two years after the end of the Civil War when Black people had not been given their full humanity and many did not yet know that legally, enslavement had ended. It also ushered in Jim Crow and continued segregation and dehumanization.

“The parallel with today is there has to not only be an announcement of change, but the action of change. This Juneteenth we should think about what was it intended to commemorate: What did freedom look like over the past 155 years? Freedom for whom? What is freedom? Have we achieved it?”

Sharoni Little is associate dean and chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer at the USC Marshall School of Business. Her research and expertise centers on organizational leadership, strategic communication, and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Racism affects “where we live, work, learn, and pray”

“Institutional and structural racism is something that lingers and lasts. Even if we were able to get rid of all prejudice, even if we were able to put something in the water tomorrow that had us all wake up and not feel any racial animosity towards anybody, we would still have neighborhoods that have crumbling schools.

“Institutional racism goes to what banks will loan what money to what customers, what neighborhoods they will make mortgage loans in. It goes to the fact that a lot of black neighborhoods are close to environmental toxins. That’s why black people have a higher asthma rate; a factor when it comes to coronavirus and making it more lethal. The legacy of racism is baked into our social and economic arrangements: where we live, work, learn, and pray, the quality of the air we breathe, the food we eat, the health care we get — it permeates every nook and cranny of our collective social existence.”

Jody Armour studies the intersection of race and legal decision making as well as torts and tort reform movements as the Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at USC Gould School of Law.

Contact: armour@law.usc.edu

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence