By Ivan Walks, M.D. | Charles D. Ellison

As the first coronavirus vaccine shots are being administered, there is quite a bit of talk and anticipation around whether it’s safe and how fast we’ll get it. We’re definitely asking lots of questions about how we’ll be distributing that vaccine, who will get it first and if our already stressed medical supply chains can handle distribution and storage.

Fortunately, there is even a robust conversation on how government (state, local and federal), health professionals and vaccine manufacturers must gain the trust and confidence of justifiably skeptical Black and Brown communities.

According to one recent (and not so surprising) national COVID Collaborative survey, just 14 percent and 34 percent of Black and Latino respondents, respectively, trust the coronavirus vaccine. This is particularly worrisome because COVID-19 kills Black and Brown folks at a much higher rate. For Black populations, the legacy of medical violence is a long one and will not go away – public leaders and elected officials must tackle it.

Yet, one major question we may get blindsided on is this: who will get the “best” vaccine available … and who won’t?

It’s that tricky, age-old question of premium versus basic. Gold versus bronze. Brand name versus generic. Americans have a constant pre-occupation, sometimes warranted, with whether or not they’re getting the best product or if they’re forced into making tough choices based on cost, quality and, many times, bias. Because of the rather narrowed and incomplete way we’ve been having the national coronavirus vaccine discussion, many have assumed it’s just one type or one standard of vaccine. If we let headlines and cable TV talking heads tell it, there’s a public sense of the big singular “vaccine” and that it’s “… 95 percent effective.” However, most of us in the know have failed to focus on one major detail: there’s not just one vaccine, there are several … and not all coronavirus vaccines are created equal. Nor are all those vaccines 95 percent effective.

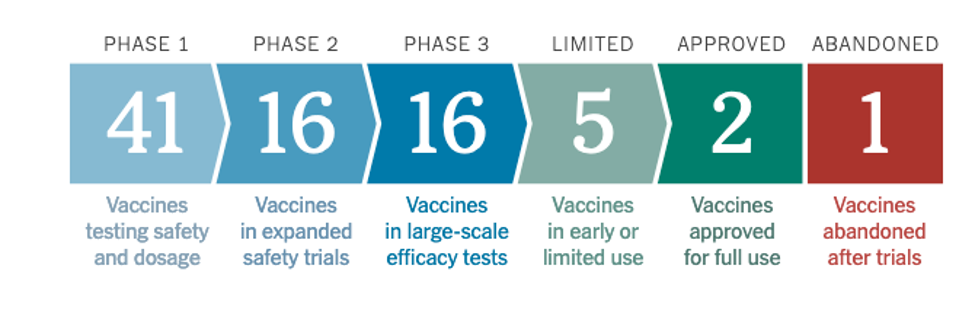

Starting this week, we have watched with a mix of nervousness and fascination as healthcare professionals have received the first administered doses of vaccine. According to the NY Times Covid-19 vaccine tracker, 2 vaccines have been approved for full use and there are 16 vaccines from different pharmaceutical makers and labs all around the world in final Phase 3 “large scale efficacy tests.” About 5 are in “limited use” as we speak.

Of those in Phase 3 or emergency use that are beginning to reach supply chains for use in the United States are Pfizer, Moderna and Astra Zeneca; Pfizer has already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use. Both Pfizer and Moderna show 95 percent effectiveness. However, AstraZeneca, reportedly, has only seen “moderate” effectiveness, with trial efficacy ranging anywhere from 62 percent to 70 percent and sometimes 90 percent, depending on the level and sequence of dosage.

That’s not to say AstraZeneca’s vaccine is not effective. Indeed, trial studies show that it is. But, when a weary public only sees the percentages, we have not yet had that honest, open conversation about how two vaccines – Pfizer and Moderna – appear to significantly outperform one other vaccine, AstraZeneca, and maybe others. In a situation like that, as vaccine is gradually available, people are going to ask questions about if they are getting the “best” vaccine. More alarmingly, we will also find ourselves in a situation where governments and medical institutions may distribute a type of vaccine based on zip code, income, health insurance and, some will wonder, race.

Bad enough we see a rather high number of people in certain demographic groups who don’t trust the vaccine. Why add to those fears with extra anxiety over vaccine quality? We need to get ahead of that inevitable conversation and potential clash right now. The fear is that vaccine distribution or, rather, who gets what grade of vaccine will be determined by where they live, how much they make and the color of their skin. Expectations on vaccine supply have already been dramatically reduced as we’re now finding out the current administration didn’t prepare for or bother to purchase the “several hundred million doses” of Covid vaccine it promised – instead, states are planning for just less than 40 million doses to start with. We’ll only have a limited supply of that 95 percent effective Pfizer and Moderna, but initially – and likely – a greater supply of the potentially 70 percent effective AstraZeneca. So, what happens when word gets out that the 95 percent effective vaccine will be used up before certain communities or populations can get in line?

It’s a valid question because we see it unfolding every day in the delivery of our healthcare, particularly as well researched and documented bias – consciously or not – often drives healthcare decisions. What we know is that race and income oftentimes dictate level and quality of care. We know, for example, that Black and Latino patients face numerous barriers to needed prescription drugs: Black and Brown children were found less likely to receive antibiotics for respiratory infections than White children. If this is a norm, why should those populations expect the equitable distribution of coronavirus vaccine?

That’s the critical question I’ve seen unfold in terrible and tragic ways firsthand. As Chief Public Health Officer for Washington, D.C. leading the response to the first bioterrorism attack on our nation’s capital back in 2001, I had to explain to outraged Black D.C. postal workers why they were receiving a different and thought-to-be cheaper Anthrax antibiotic, doxycycline, compared to the Ciprofloxacin that was being taken by mostly White Capitol Hill personnel and postal workers in Manhattan. Two Black postal workers had already died from Anthrax and people wanted answers and optimal healthcare. Yet, the decision to pick “doxy” was based, ultimately, on risk vs. benefit, not cost …. difficult to explain in a setting of disparate mortality along racial lines.

We might very well be headed down this same road in the distribution of coronavirus vaccine. Even as we resolve the question over trust – since various public and private institutions may eventually mandate Covid vaccination as a condition of travel, employment and schooling, anyway – we’re going to hit the thornier topic of quality. How vaccine is dispersed could potentially come down to bias selection: the battle between haves and have-nots. What we need to do now is have as much of a transparent conversation about these vaccines as possible and include the talk about vaccine efficacy as part of the overall conversation on closing the trust gap, especially as it relates to Black communities.

To ward off the dramatic and dangerous levels of skepticism from that, public health professionals and elected officials must be honest. Let’s get out in front of this: 1) we now know we’ll have limited vaccine supply to start off with and 2) our medical and emergency supply chains, including the cold storage needed to preserve the 95 percent effective Pfizer and Moderna, will also be limited. Hence, there will be heavier reliance on the 70 percent effective AstraZeneca which, incidentally, doesn’t likely need the cold storage.

Policymakers on all levels should immediately huddle with public health officials and consider measures to prevent vaccine distribution that would appear to be based on income, healthcare access and race. All approved vaccines, regardless of proven or perceived quality, must be distributed equitably. As we attempt to navigate our nation out of this pandemic, let’s ensure our historical and ongoing national biases don’t further ruin the path to total recovery.

IVAN WALKS, M.D.is the former Chief Public Health Officer of the District of Columbia and Principal of Ivan Walks & Associates.

CHARLES D. ELLISON is Senior Fellow at the Council of State Governments Eastern Regional Conference’s Council on Communities of Color and Publisher of theBEnote.com

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence