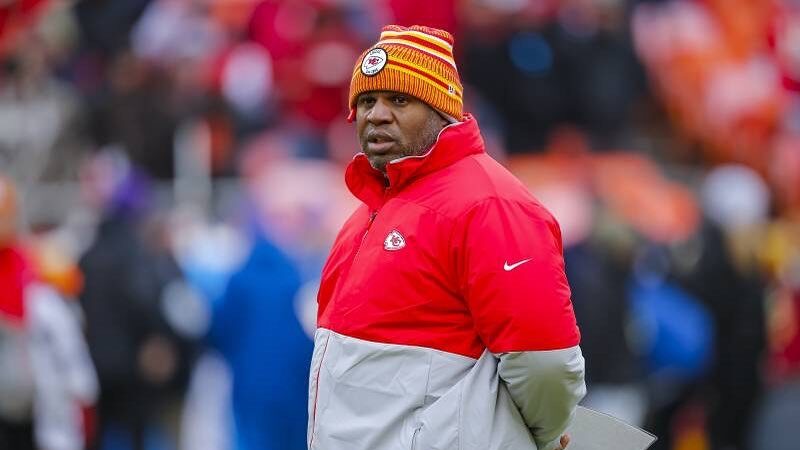

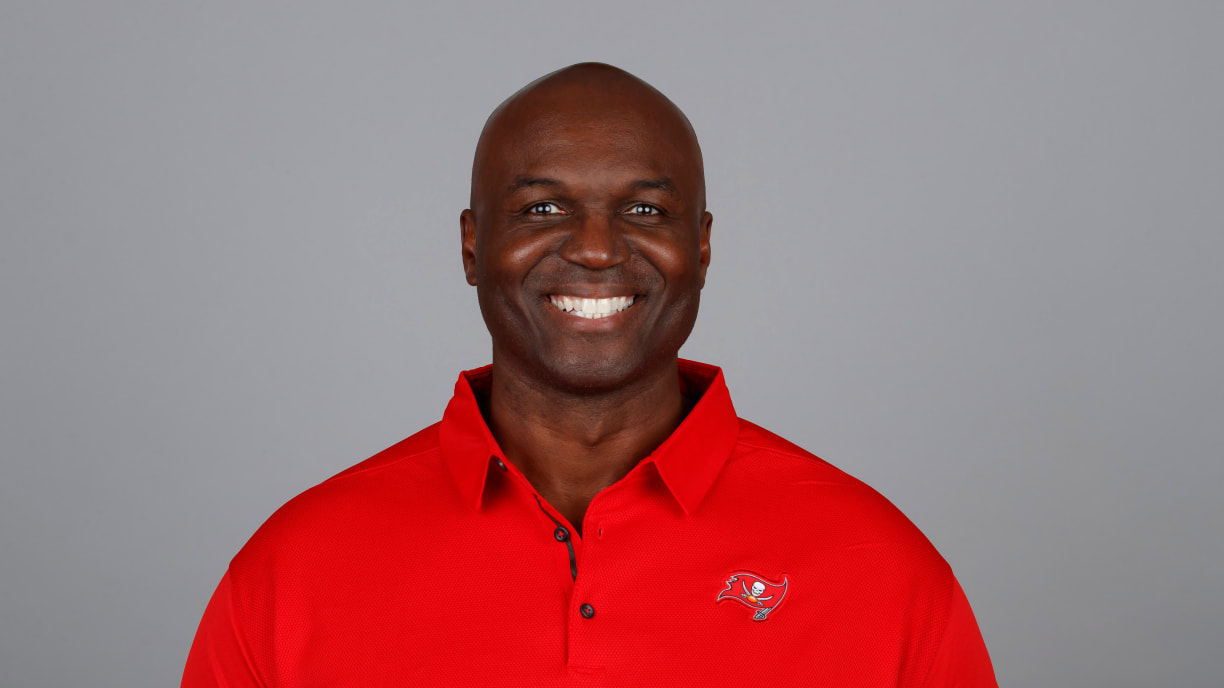

Lost somewhere behind the battle between the two quarterbacks, there will be another that may do more to define the outcome of Super Bowl LIV: Tampa Bay defensive coordinator Todd Bowles is charged with the task of trying to slow down the Kansas City Chiefs offense coordinated by Eric Bienemy.

It may be the least discussed matchup in the battle for this year’s Vince Lombardi Trophy.

Both coordinators were highly respected candidates for the seven vacant head coaching jobs when the regular season concluded in January. But neither was hired. Instead, despite a shift in hiring practices in the NFL over the years, nepotism and the “good old boys” network continued to put up barriers to the head coaching role.

In fact, in a league where approximately 70 percent of players are black, the NFL’s 32 teams opened the 2020 season in September with only three black head coaches. By the end of the regular season, there were seven openings — but only two minority coaches were hired. Bowles and Bienemy were left on the outside looking in.

Having Bowles and Bienemy as coordinators on the NFL’s biggest show serves to illuminate the plight of African-American coaches today: Despite their success as the two most important assistant coaches for championship and contending teams, they continue to be overlooked for head coaching vacancies throughout the league.

Bienemy is still waiting for his chance after being labeled a candidate who “doesn’t interview well,” while Bowles hopes a second chance for redemption will allow him to prove he learned from previous experience.

“It’s never going to change until you have an African American as one of the 32 [team] owners,” said Rick “Doc” Walker, who won Super Bowl XVII with the Washington Football Team.

“You can’t fix a problem when the heads of state turn their noses up at them,” he said. “It’s a joke.”

The two coordinators are not short of credentials.

Bienemy’s offense has won three consecutive AFC West Division titles and back-to-back conference championships, and he is now on the precipice of a second-straight Super Bowl victory. Meanwhile, Bowles had to return to the sidelines as a defensive coordinator for Bruce Arians in Tampa to rebuild his credibility following his tenure with the New York Jets, which has become a wasteland for head coaches of any color.

“I would tell [Bienemy] to stay in Kansas City and create something we’ve never seen before since the job he gets will have bad ownership and no talent,” Walker said.

“It’s like going to the movies where the black character is the first to die.”

The stigma of either “not interviewing well” or underachieving against perilous odds continues to be the undoing of coaches like Bienemy and Bowles.

For instance, current Tampa offensive coordinator Byron Leftwich wasn’t even offered an interview during the most recent hiring cycle — though he was preoccupied with helping construct the offense that Tom Brady led to the NFL Championship game.

“If you took someone out of their white privilege environment and brought them into an urban environment how would they interview?” asked Walker. “It’s not about black versus white, its right versus wrong.”

Coaches with experience navigating the dysfunction of unsuccessful franchises, such as Bowles with the Jets, often find it difficult to gain a second opportunity like their white counterparts. Bowles, for instance, finished with a 26–41 record in New York and now can only hope that if he wins the Super Bowl he might be the next addition to the island of recycled coaches.

Previous success also doesn’t seem to matter when trying to make the second-chance list.

Jim Caldwell was the last coach to lead the Detroit Lions to the postseason.

Caldwell, who succeeded Tony Dungy with the Indianapolis Colts and led them back to the Super Bowl XLIII, is 62–50 overall with two losing seasons in seven years. He was fired by the Detroit Lions after finishing with a 9–7 record. He had one losing season in Motown and made two playoff appearances, leaving with a 29–19 mark after four years. His replacement Matt Patricia won just 13 total games in two and a half seasons.

He was fired 11 games into the 2020 season at 4–7.

After producing sub-.500 records, few are recycled through the system of network familiarity, where friends often look out for compatriots who get quick chances to rebuild their brand with immediate coordinator positions, allowing them to fast-track for second or third chances at being head coaches.

According to an Arizona State University study, the number of head coaches of color has fluctuated since the Rooney Rule was implemented in 2003. The Rooney Rule, named after Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney, mandates all teams must interview at least one candidate of color for any head coach or front office position.

“I’d like to see them do away with the Rooney Rule,” said Walker. “It’s embarrassing. You shouldn’t have to force people to routinely make bad decisions to have to make one.”

The ASU report, “Field Studies: A 10-Year Snapshot of NFL Coaching Hires”, analyzed hiring trends and looked for patterns over ten years, from the 2009–10 NFL season through the 2018–19 season.

The findings were damning.

It concluded: “Head coaches of color are hired at older ages, have more significant and relevant playing experience and do not receive equivalent ‘second chances.’ Specifically, when African American head coaches have been fired in the NFL, it has been more difficult for them, as compared to white coaches, to obtain another head coaching position at the same level.”

(Edited by Kristen Butler and Alex Patrick)

The post Struggle For Black Head Coaching Opportunities Continues In NFL appeared first on Zenger News.

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence