When Will More Than $2.7 Billion The State Has Invested in Fighting Homelessness and Building Affordable Housing Reach the People Who Need it?

By Tanu Henry | California Black Media

When Coleen Sykes Ray started an organization with her daughter in 2015 to help homeless women, the Stockton, California resident had no idea she, too, would be homeless four years later.

Now, she, her husband and two children live in an Extended Stay America hotel in Stockton. The family pays a costly $610 hotel bill every week as they struggle to find a place to live.

“When you tell landlords you have a Section 8 voucher, its like saying a dirty word,” says Ray who is African American and works as a Community Outreach Specialist for a local public health organization. “It’s heartbreaking because we’re good people. I’m working and I’m college-educated.”

Ray says she gets why landlords refuse to rent their properties to her family. Some of them explain that they have been burnt many times by people who pay them with vouchers. Other property owners, she says, tell her that it is a hassle to have to deal with the Section 8 administration.

But understanding the landlords’ reluctance – after going great lengths to impress them, only to be rejected in the end – doesn’t make life easier for Ray and her family. They live cramped in a single hotel room, preparing almost every meal in a microwave, with no sign in sight that they will have a new home soon.

From 2017 to 2019, the number of homeless people in San Joaquin County, where Stockton is the largest city and the county seat, tripled, increasing from 567 to more than 1,500. During that same period in the city of Stockton itself, the homeless population skyrocketed, too, reaching 921 from 311 people two years prior, according to a 2018 “point-in-time” census report compiled by San Joaquin County.

“While we certainly understand that the number of homeless people have tripled in the county, that number might not be a true reflection of what has happened over the last two years,” says Adam Cheshire, Program Administrator for Homeless Initiatives in San Joaquin County.

Cheshire says in 2017, there were only 35 volunteers who signed up to help count San Joaquin’s homeless population. In 2019, there were 400 volunteers, which helped his organization achieve a more accurate count, including the unsheltered homeless population.

Homelessness is not just a problem for San Joaquin county. It’s a statewide issue. Every major city in California has been hit by the crisis. Across California, the homeless population jumped by 16 percent between 2018 to 2019. With a total of about 130,000 people without a permanent place to live, California has the largest homeless population in the United States.

The high number of people in California without stable housing or a permanent address poses a serious problem for the state as it takes steps to avoid an undercount in the 2020 Census.

For African Americans, California’s homelessness crisis is even more severe.

“Black Californians make up nearly 7 percent of the state’s general population yet are nearly 30 percent of the homeless population,” wrote Mark Ridley-Thomas, a member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, in an open letter to Gov. Newsom in June. Ridley-Thomas was reaching out to the governor asking him to address some of the problems specific to African Americans in the state.

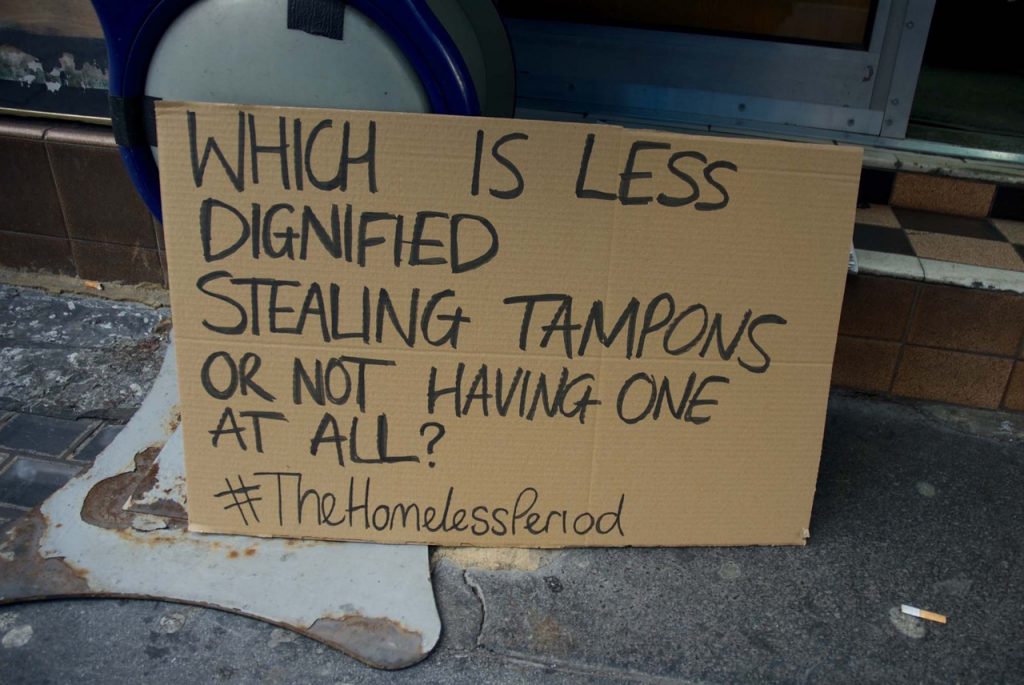

As the homeless problem started to become more noticeable in Stockton, Ray says she and her daughter would see women, some of them mentally ill, walking around “free-bleeding” during their menstrual cycles. Disturbed by what they saw, they decided to package bags of women’s sanitary hygiene products – washes, wipes, tampons and napkins, etc. – and hand them out to homeless women.

Soon, what they began as a one-time goodwill gesture grew into a non-profit they started and still run called Bags of Hope. In their first year, Ray and her daughter handed out 30 bags of the feminine products every month. Between 2017 and 2018, as the homelessness crisis spiraled in their city, they donated about 65 bags every month to homeless women in Stockton. This year, Ray says they have been fortunate to reach about 100 women living in shelters and on the streets every month.

Most of the funding they use to buy the products comes from donations from local businesses and individuals and a gala they hold once a year. The biggest gift their organization has received so far came from the Black Employee Network at Proctor and Gamble.

“Doing the work of Bags of Hope is a kind of ministry,” says Ray. “Helping other homeless people, gives me and my family hope now that we find ourselves in the same situation. There is no reason to be ashamed. We are not homeless because we are bad people, bad parents or we are lazy. There are investors, buying up properties in neighborhoods, raising the cost of housing, and pushing people out of places where they have been living for years.”

Ray, her husband, daughter and son, who is autistic, became homeless in May of this year. It was about eight months after Blue Shield of California laid her off last September along with about 400 other employees.

Ray’s husband is a diabetic who became permanently disabled seven years ago after doctors amputated one of his feet following an injury. After her layoff last year, the couple scraped up money together to continue paying their $1,200 monthly rent – until January.

That’s when the landlord increased their rent to $1340, which Ray says they “simply could not afford.” After getting help from her church and making payment arrangements with the landlord for the next couple of months, the family fell behind on rent payments and agreed to move out.

Because every apartment or house they looked at before they left their rented home cost between $1,500 and $1,700 a month, the family decided to move into the hotel where they currently live.

Fortunately for Ray, she landed her current job on June 24, this year.

But with the high weekly hotel cost, almost “every dime we earn,” says Ray, from her salary and her husband’s disability payment, goes toward their hotel bill.

Around the time Ray and her family moved into the hotel in May, Gov. Newsom presented his revised 2019-20 budget to the legislature with unprecedented spending in it to take on the state’s homelessness crisis. The state plans to invest approximately $2.7 billion on shelters, prevention, support services, and more, as well as funding new affordable housing initiatives, according to Christopher Martin, Legislative Advocate for Housing California, a Sacramento-based organization focused on helping to solve California’s homelessness problem.

The budget took effect July 1.

Then, two weeks ago, Gov. Newsom signed into law AB 101, a trailer bill detailing budget dollars and issuing guidelines on how the monies allocated to fight homelessness will be spent. A provision tucked into the bill now prevents local governments from blocking the building of homeless shelters and navigation centers in communities across the state.

A few of the budget items in AB 101 are: a $45.9 million allocation to support Census outreach to hard-to-count communities; $25 million to support housing and benefits for homeless people who are disabled; and $16.4 million in rental assistance for former prisoners .

About $250 million in the state budget will be funneled to counties across the state to fund homeless initiatives.

Together, California’s counties and cities will receive a total of $650 million from the state over the next year for homeless housing, assistance and prevention programs.

Cheshire told California Black Media that his team is coming up with ideas for the most effective ways to spend the new state funding in San Joaquin County so they can help families like Ray’s. But it is still too early, he says, to share those plans because they are not yet finalized and the state has not yet released the money.

Most of the money will start to kick in after April of 2020, says Martin.

As Ray balances adjusting to her new day job with the difficulties of being homeless, and helping other homeless women through the work of Bags of Hope, she remains upbeat and optimistic.

“I can’t go out and preach love, light and strength and have a negative spirit,” she says. “No matter what I’m facing.”

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence

Westside Story Newspaper – Online The News of The Empire – Sharing the Quest for Excellence